The Self-Preservation Continuum

An analytical model of self-treatment and awareness

In many ways, the recovery process is a human rite of passage. To varying degrees of severity, all people born into physical form must suffer the archetypical fall from grace, after which they are granted a chance at redemption. Through subconscious influence or lack of actionable power, many remain stuck within a spiraling abyss, occupying their precious tenure in the school of life with monotony, misery and existential dread. Others undergo a mythological narrative arch known as the hero’s journey, during which the protagonist bears witness to some darkly laborious venture which strains the foundational fabric of his character, only to return home transfigured, invigorated, infused with a newfound sense of purpose. Having survived this predestined visit to hell, our hero is endowed with ancient wisdom, posed to surrender his metaphorical torch to subsequent generations.

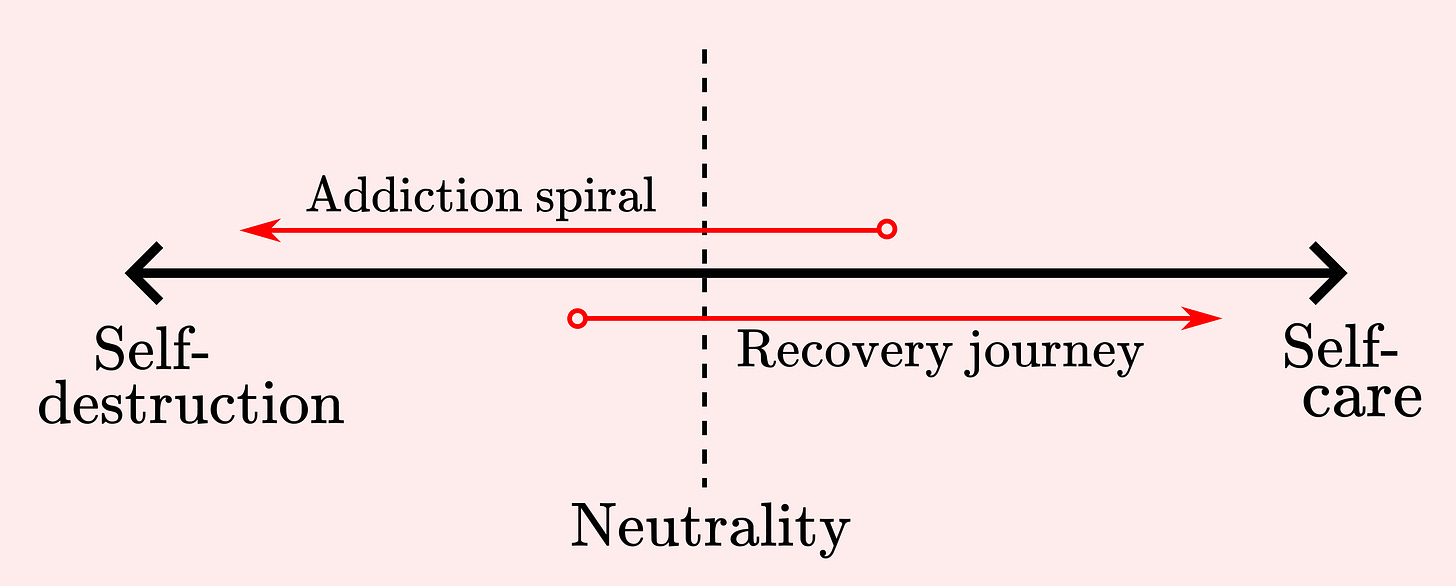

This tale resonates within me, for I have known extended durations of twisted suffering and, by enduring it, I have seen transformation take seed in the fertilizer of agony. I liken my path to one of self-preservation, in that I would historically undulate between gritty survivorship—atypical tactics and cunning placement—and mindless escapism, manifested into pure obliteration. Two key features, along with their diametric counterparts, constitute an axiomatic container for the conservation of oneself: self-care and awareness. The former is a pop-culture icon, the topic of myriad self-improvement books and holistic workshops; the latter is best understood through its opposite—complacency, a fundamental concept in domains of industry and engineering that is analogically applicable to addictions and mental wellness.

Self-care, in its most rudimentary form, is the innate ability of an individual to provide for themselves basic necessities such that a healthy internal ecosystem is sustained, ideally yielding a state characterized by safety, security and love. Its antonym is self-destruction—a complex affliction in which choices and habitual leanings of one’s ego-structure act in overt detriment to the preservation of self, both psychologically and biologically. A person in active addiction is traditionally ripe with self-destructive tendencies; thus, the journey toward wholeness and recovery is one of fostering and enacting self-care in replacement of deteriorative conduct. Similarly, as one descends from an environmentally-gifted baseline of self-care into injurious undertakings, thoughts and inclinations, they are effectively traversing an addictive downfall.1 From this parallel a spectrum is illustrated, one that is uniquely calibrated on an individual level yet generically useful for all conscious, thinking creatures—the individuated self-treatment scale as I will denote it here.

One could postulate that either of these linearly portrayed trajectories could be assigned to the majority, if not all, of humankind’s subjective, present-moment experiences. This would suggest two underlying tracts—growth and devolution—along which any arbitrary person may travel.2 This distinction is akin to one put forth previously on Astral Projections; namely, that all people are perpetual inhabitants of either sickness or betterment. Here, betterment is synonymous with enhancement of self-caring methods and attitudes, not only as observed through maintenance of physical health—adequate sleep, nutrition and exercise—but through upkeep of psychic equilibrium, gauged by highly-personal metrics such as: relationship to self, capacity to regulate, enjoyment of isolated self-presence, internal organization, goal orientation and sustainability of mental peace. Sickness, therefore, is aligned with the degradation of such matters.

Complacency, another human-metric intrinsically woven into recovery and destruction progressions, is explained most straightforwardly through use of an industry example. More than 10 years ago, I worked as an operator in a field of sour hydrocarbon-producing wells, an inherently dangerous environment that is critically dependent on the mental stature of those who serve within it.3 Unfortunately, a veteran worker had been killed just days prior to my arrival—the cause of death was, ultimately, complacency. Oil pipelines are cleaned by a process called “pigging” where cylindrical pieces of plastic are impelled in the bulk direction of flow to scrape away deposits of wax and asphaltene. Extracting such contraptions is a risky endeavor, requiring an intimate understanding not only of the particular pipeline-trap installed, but of pressure. Occasionally, a parcel of built-up pressure gets “caught” behind the pig which may, if not properly drained before opening the pipe, be released into the atmosphere with incredibly high velocity (~100s of feet/second).

As is often the case in industrial accidents, the lost worker had been performing this routine job for decades—a major risk factor, as dictated by unadorned human nature. When people complete tasks over and over, for years, they begin to forget (or at least think less about) the intricate and perhaps complicated details involved. We take for granted things we do regularly—motor vehicle operation being the most apparent example—and our bad habits, as miniscule as they may have been when we first began, compound over time and transform into a critical, serious error waiting to occur. In fact, I would speculate that competently trained new workers are statistically less likely to induce life-threatening industrial problems than their matured colleagues, whos chronic mannerisms have calcified.

For ages this man had carefully lived by the customary “line-of-fire” platitude until finally that judgement lapsed and he inadvertently got caught in the crosshairs of a loaded cannon with 6-inch wide, solid bullets. The “pig” struck his chest and crushed his internal organs, killing him instantly. As morose as this story is, it perfectly depicts the creeping, complacent propensities associated with human behavior—especially that which is mundane and unchanging. Standardized actions cannot casually be deemed unimportant. Consider driving—from properly checking blind-spots to wearing a seatbelt, there are countless iterative micro-processes that, as a whole, compose the act of running a vehicle. If even one of those components are faulty—wrongly learned or treated with apathy—time superpositions this defect until, eventually, it is magnified to the point of potential total system failure.

As previously mentioned, the intuitive opposite of complacency is awareness. A refreshed sense of methodical focus can mitigate hazards present in the natural course of complacent decline. This is the precise motivation for company-wide safety-shutdowns centered on complacency, as was incurred after the passing of my should-have-been coworker. Complacency does not correlate with a lack of competency; rather, competent people require regular segments of re-teaching, either through their own means or under hierarchal, risk-aversion structures designed to identify areas of weakness and plausible human-automation. The most elementary fragments of working motion can morph into sources of sinister consequence—for this reason, self-assessments must be routinely employed to ensure that simplistic areas of action are not souring into probable causes of damage.

These concepts are readily extrapolated into our discussion of self-treatment in the context of addictions and mental health. One may intuit that complacency is ubiquitous in addiction and thus belonging to the destructive end of the self-treatment spectrum; however, such an unambiguous label is overly reductive—even if it fits the majority of addictive phenomena. There are cases of self-aware—even premeditated—self-destroying affinities, thus bringing forth the integral ideology known as harm-reduction. Within my scope of knowledge, harm-reduction is defined as the necessary utilization of psychoactive substances or escapist practices to salve an enslaved or unsafe inner landscape which lacks the imperative resources to survive otherwise, doing so to subsist until genuine help arises, prescribing a least-of-evils approach to lightly tread the fine-line of “just bearable” rather than diving deep into hedonistic bliss.4

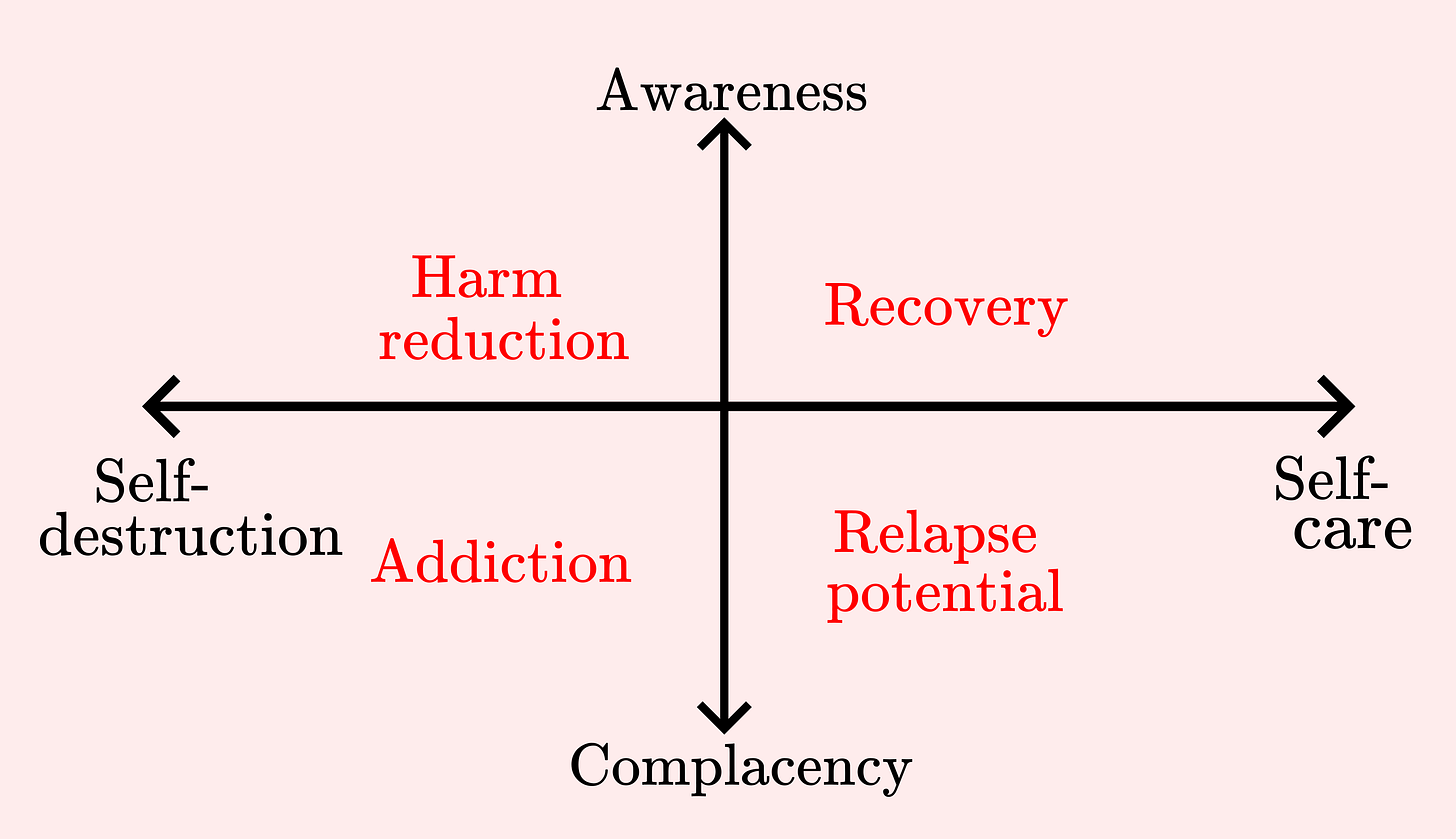

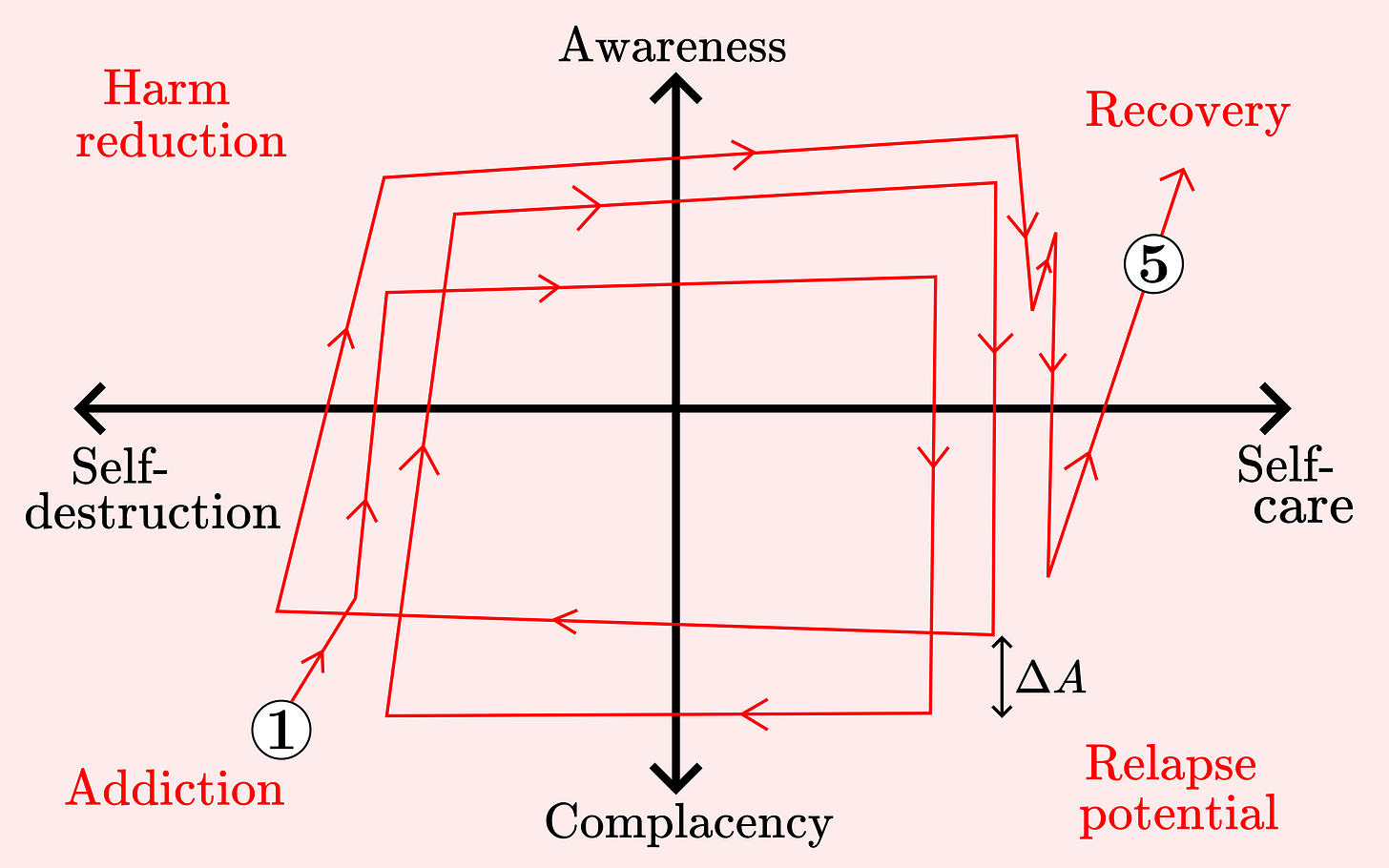

Equivalently, one can exist passively in a self-caring lifestyle, upholding sobriety and refraining from eroding their physical, emotional and spiritual bodies, yet still be complacent in their program-of-action. This positionality may be considered one of high relapse-potential; however, the common phrase “dry-drunk” also fits. Here, once practical tools have faded with respect to held intrigue, lessened in significance such that they function at a fraction of their original strength, leaving the individual exposed and vulnerable to threats both from within and without. The glorious luster that, at first, coated the confines of the addict’s conviction have paled to a dull grey—nothing seems appealing, life-saving conventions have fallen into mechanization leaving the user bored and yearning for some deviation from normality.5 The aforementioned sub-cases—harm-reduction and relapse probability, serve to construct a comprehensive grid of plausible user-states. It is termed the generalized self-preservation continuum and is shown below.

One could simultaneously argue that awareness—or lack thereof—is paramount in the successful establishment of self-caring ideals, and therefore inseparable; however, retaining awareness and care as their own independent spectra creates a far more practicable tool. The care-axis quantifies one’s way of living while the awareness-axis gauges conscious engagement with their surroundings, regardless of whether they are nurturing or otherwise. I myself have intermittently occupied each of the elucidated four sectors—thus of obvious interest to the struggling addict is a framework of transitionary criteria that illuminates commonly trodden paths within the limits of this plot. A hypothesized version, constructed through contemplation of authentic experience, is realized below.

Addiction encapsulates the initial conditions of this cycle—for sake of exhibition, we assume that this state was reached through no purposeful fault of the user. Life’s initial trajectory has situated the individual in a deeply nested chasm of self-ruinous behavior; furthermore, they are unaware (or in denial) of their inherited depravity—self-harming actions have become ritualized, reflexive, a product of upbringing within a constitutionally sick society. Immediate gratification has been conditioned on a cellular level, leading the user to fully accept, if not embrace, their abruptly harmful nature as it is truly all they know, both for themselves and those around them. Note that this analysis is not restricted to substance abuse—the whole of culture is more addicted than ever before, be it to alcohol, sex, smartphones or mindless, surface level socialization.

Generally, movement from states 1 to 2 must be catalyzed, usually via some tragic happening that acts to devastate the individual. Since they are unequipped to handle the resultant inner and outer turmoil in wholesome ways, their addictive girth widens, skyrocketing consumption and opening doors to foreign and more effective modes of numbing. No external scheme of self-appeasement is sustainable, however, so the user soon faces greater magnitudes of suffering. Pain, the humanistic cohesive, is an outstanding accelerant for personal change, causing lateral diffusion and remarkable outreach toward available support beams, leaving two possible outcomes: the addict either a) continues further into gratuitous self-abuse until they reach a new global minimum, causing the crossroad to reappear, or b) admits defeat and accepts some deliverance of external assistance, the efficacy of which is a function of their fortune and privilege within the wider communal architecture.

For the average middle-status drug addict, an opportunity for positional transference is often revealed that places them into a stabilizing microcosm—a rehabilitation facility, for example, or a harm-reductive group. Those lesser submerged in the spectrum of debauchery need less intensive interventions; the specifics of change-inducing mechanisms are unimportant, however, at least for the purpose of interpreting this model. Now, the user begins to work on themselves, building new tools for inner world management, applying paradigms for unwinding childhood programming, and crafting inter-relational bonds with likewise others to combat their engrained sense of mandatory isolationism. They gradually shift into a more enlightened place of being, further harnessing available resources and the ever-present gift of desperation—still-burning imagery of a miserable life recently departed—until they reach a jumping-off point: reintegration into macro-society or the beginning of a new chapter represented by the line connecting points 2 to 3 in the prior figure.

Keeping with the picture of a modest drug addict, this point may be envisioned as the last day of a multi-week stint in an inpatient treatment center. Professional help—the whole ordeal, really—has officially woken them up and a freshly instilled vision lures them forward into what is hopefully an updated way of living. They have been supplied a set of viable new skills but they have not yet employed them in non-augmented reality; thus, the real work begins.6 They are thrust back into the cutthroat, often cold world, no longer blissfully ignorant, nor willing to utilize the destructive methodologies that drove them into their previous nightmare. They have reinvented themselves, with some much-needed assistance, and they slowly forge onwards, upwards, gaining traction one day, one hour at a time, absorbing the strength and resilience of their new peers, painstakingly laying a brand new foundation of existence.

Moving from points 2 to 3 is an epic odyssey, requiring months, if not years, of diligent patience as the user slowly acclimates. For some, resolve is of diminishing proportionality to the length-of-passage since their last bottom—those at late-stage evolutions of addiction are more blessed at this point, for the emotive disruption tied to their history is dependent on the severity of witnessed trauma, suffering and situational damage. Inch by inch, the addict claws their way up the mountain of salvation as horrible sensations of their past become nothing more than a story, their future looking brighter than ever as glimpses of serenity and stability flash through their periphery. Inevitably, the addict reaches a plateau—an impasse of sorts—where their localized potentiality peaks, demanding further generative impetus to negate an impending decline.

This is point 3 in our figure, representing a time when the majority of users start to regress, particularly those in early-passes through the preservation cycle. Here lies a stagnancy in the care-axis with rapidly decreasing awareness—the addict’s newly found life has suddenly lost its marvelous shine as instilled soul-saving practices become second-nature—the spark inside is snuffed, leaving their bare spirit craving something different. Advanced users—survived end-stage addicts, for example—may recognize this mutation as mere deviation from a desired level of consciousness, exploiting that knowledge to course-correct and return to a baseline level of perception, perhaps enhancing their self-caring systems as a byproduct (shown as a dotted line between points 3 and 5). Most people—myself included—require multiple passes through the self-preservation cycle, each time strengthening a foundational layer of counter-complacency and deepening their reach into the destructive axis.

Point 4 is a climactic threshold where the individual’s accelerated loss of awareness culminates into an explosive alteration—for drug users it is a moment of relapse as protective barriers have weakened beyond repair and defense-mechanisms are rendered futile. Alternately, it can be a pivotal instant of positive reconstruction, provided that a perfect combination of circumstance and fortune shock the person back into conscious wakefulness, propelling them upwards into a glorious return to self-aware recovery. This is a crucial point of reckoning—fate differentiates whether the user is sent for yet another hardship-growth cycle or transported back into affirmative discernment, plausibly having stronger developed self-caring tendencies due to a renewed sense of gratitude and risk comprehension.

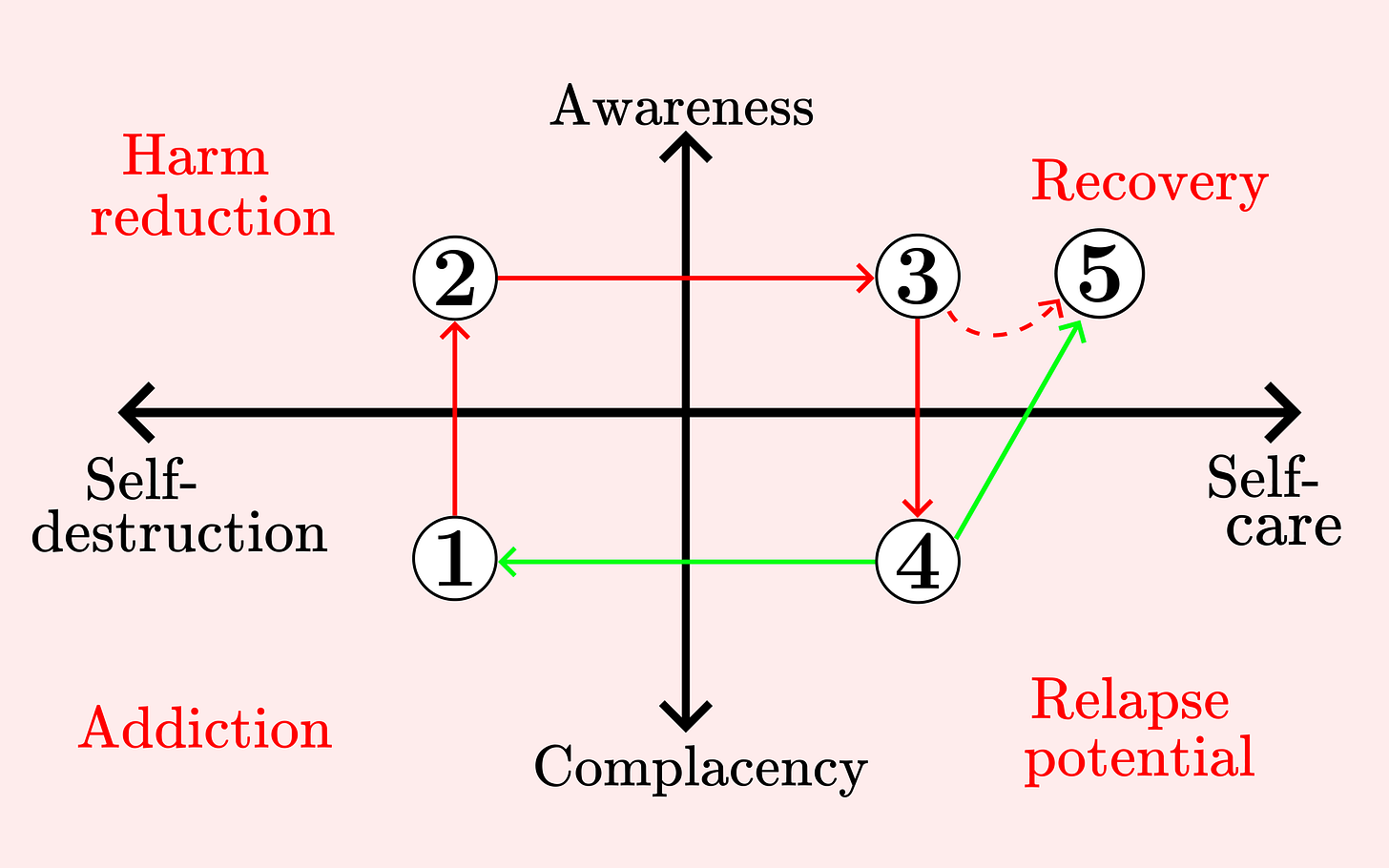

This model is an idealistic vision of an intensely complex, personally-tailored process, generalized around a core of human automatism. In reality, on the journey toward wellness one circumnavigates many corners of the derived continuum, translating along hyperbolic curves of oscillating self-treatment and garnered awareness. Regardless, it is useful to simplify the hereditary complications of human operation into their distilled essence, allowing ease of digestion and practical implementation. Beauty lies in the act of collapsing complex movements into their most elegant constituents, and to further demonstrate this notion I have developed a more realistic plot on the same axes that captures a real-life transition through varying degrees of self-treatment and awareness, shown in figure 4 below.

ΔA signifies a layer of awareness added to the individual’s psychic foundation as a result of enduring a full cycle through the continuum’s 4 quadrants. This effect is subconscious—as they fall backwards into complacency and thus self-destruction there lingers a modicum of learned perceptivity which involuntarily presents itself in the user’s actions. Note that figure 4 remains a simplified scenario—one’s true care-awareness function on the journey to recovery would be riddled with twists and non-linearities.7

In writing this article I have attempted to shine a light upon certain natural forces that act on human beings brought up within a dysfunctional society, especially applicable to the inertial drug addict. To obtain a basic understanding of underlying principles allows us to disfigure and reroute our own trajectories whilst already being disposed within the dynamic environment that contains them. My motivation stemmed largely from a solemn reflection upon my own past, reimagining the many terrible trials and compressions I somehow survived, wondering if my suffering could have been alleviated with a degree of knowledge around the tornado-like pattern I was caught within. Awareness of natural complacent tendencies is the most profound antidote for complacency itself; and, comprehension of self-destructive spirals offers an opportunity to apply root-cause analyses and fortify safeguards to maintain harm-reductive techniques, thus lessening the reached depths of self-annihilation.

The self-preservation continuum outlined here is an alternative restoration of the historic hero’s journey, updated for modernity by placing addiction in the role of primary antagonist. Recovery is a multilayered intrapersonal struggle that systemically involves the physical, mental and spiritual planes—through collective efforts toward thorough characterization, we can amplify and extend our healing capacities and thus maximize our worldly expressible potentials, hopefully guiding us closer to a unified field of enlightened consciousness. This is a noble endeavor that requires commitment from all ranges of social status—any belief infrastructure that views addiction as moral ineptitude must be conquered by science- and logic-based philosophies. We all carry the ability to ascend in spite of cultural conditionings that otherwise shackle and bend us, and beyond them there is immense possibility—limitless greatness—awaiting every one of us.

* If you feel so inclined to comment on this article please feel free to do so on this note.

Addiction in this context need not be one of substance usage; instead, addiction refers to any compartmentalized facet of living that works as a mediated escape from the realities of life. It is a glaring symptom of inner turmoil expressed in outward behavior.

Some may argue that a third basic state exists—stagnancy, or going in neither direction—but I would argue, and I am not alone in this sentiment, that staying stagnant is generally equivalent to going backwards.

For those who do not know, the term ‘sour’ in the oil & gas world means “containing H2S.” H2S is hydrogen sulfide, an extremely toxic gas present at in situ (virgin) reservoir conditions in many hydrocarbon fields. Concentrations as low as 1000ppm (parts per million—particles of H2S per million particles of air/particulate mixture) can cause immediate effects including loss of mobility, loss of consciousness, coma or death.

Examples of harm reduction: using kratom rather than fentanyl, obtaining a harm-reductive physician to obtain stimulants rather than seeking similar street drugs, or regular usage of ketamine to avoid becoming deeply dependent on benzodiazepines. These matters are “grey areas” of recovery and certainly subject to discussion; however, harm-reduction is a uniquely personal topic—a method that may seem ludicrous to some may in fact be life-saving for another. The underlying principle is a conscious effort to minimize the severity and quantity of drugs utilized, rather than succumbing to constant excess and total escape from reality. One takes just enough to breathe and still feels the piercing pain of their nightmarish circumstance, subdued as it may be. In the second half of my drug-using career I would generally oscillate between strict, albeit wildly experimental, harm-reductive tactics and full-blown destructive addictions, the latter of which are more aligned with the concepts of powerlessness and unmanageability. In the context given here, harm-reduction may also refer to the intake and stabilization process of a rehabilitation center—in a literal sense, the harm potential is reduced upon entering an enforced drug-free setting.

I speak from experience, having witnessed such a change many times in the 8 years I spent pushing toward sobriety—the luxurious cloud that carries one in through the early gates of salvation quickly dissolves.

One could argue that the facilitated journey through rehab could move the user positively on the care-destruction axis; however, keep in mind that inpatient centers provide the care—the destruction may have halted but the act of laying real self-caring roots does not begin until the person walks out the door.

It is important to realize that although this model is rooted in actual experience, it is nonetheless a simplified procedural framework applied to wildly complex human tendencies, and thus it is not without imperfections. Perhaps the most pressing component of possible confusion is that harm-reduction is designed to refer to both conventional practices—maintenance usage, for example—and the process of inpatient treatment. This was made so because an addict’s psycho-situational bottom, be it localized (proceeded by a period of upward motion and subsequent relapse) or globalized (so-called rock bottom) intuitively corresponds to minimized positions on both care and awareness axes (point 1 in figure 3). Most bottoms are only escaped via external assistance; however, this model allows that the user can move out from the (likely localized) bottom into a harm-reductive lifestyle on their own which could be construed as a contradiction, although I do have personal experience in doing so. This is somewhat rectified in figure 4 in that the user goes through multiple unique cycles along the same continuum, allowing the final emersion into the negative-care and -awareness quadrants to represent “rock bottom” and the following ascent into harm-reductive territory to correspond with treatment, as was the case in my own journey.